The evening of Friday, June 17, I rose from bed at around 1 am with the urge to write about something that had happened earlier that day. On Wednesday, June 22, I was still in the process of revising that piece when something else happened that forced me to rewrite the whole thing.

On Friday, I exited the Capitol Hill light rail station at Denny and Broadway. An officer, who for the sake of this post I’ll call Sergeant Jesse (because like former WWE wrestler Jesse “The Body” Ventura, he’s built like a body builder AND eloquent enough to be a public figure), approached and asked if he could speak to me for a few moments.

Renaissance man and fashion icon, Jesse Ventura

Sergeant Jesse is maybe six feet tall, white, and has a social ease in speaking that can be both charming and intimidating to someone like myself, who often exhibits a few symptoms of social anxiety when speaking to someone new, especially if that someone is perceived to be an authority figure. Sergeant Jesse introduced himself by name and asked if I live in the neighborhood. I do. He asked if I was planning on going to any Seattle Pride events in the area next weekend. I said that I am. Sergeant Jesse pointed to the gated lot around the Broadway and John Street exit of the station and said that during Pride weekend, this whole area would be packed with folks. He asked how I would feel if, among a standard or even heightened police presence at the event, I saw an officer standing at a raised level armed with a rifle. (Actually, Sergeant Jesse first failed to indicate that the man with the rifle would be a uniformed police officer, which resulted in one of those awkward, whoopsy-daisy chuckles that have the end-result of bringing people together. That may read as sarcasm, but it’s not, and it’s a shame that I’m missing an opportunity for some A-level sarcasm right here.)

I said that the sight of a rifle would make me uncomfortable. Sergeant Jesse expressed dismay. “Really?” he said. “A uniformed police officer with a rifle? Why would that make you uncomfortable?” (All quotes are paraphrased to the best of my recollection.) I said because the sight of any gun makes me nervous. Sergeant Jesse expressed dismay again. “All police officers carry handguns,” he said, indicating his own. “Does this make you nervous?” Yes, I said. We shared another nervous/bonding chuckle and Sergeant Jesse said he would make an effort to stop resting his hand his gun while we spoke.

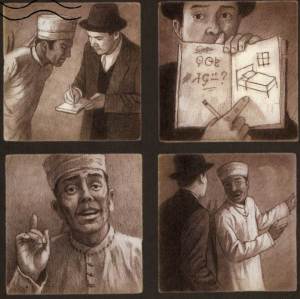

Sergeant Jesse explained his reasons for asking these questions. Sergeant Jesse did not immediately say it, but the recent mass shooting at Pulse in Orlando, Florida (among other massacres) gave him cause for concern. Sergeant Jesse explains that he got into the police force because he feels a drive and duty to protect others, and he feels he could better protect Pride attendees if he could have one (or more? He did not say, but I assume more) officers armed with rifles at the event. I asked Sergeant Jesse why a rifle and not a handgun. Sergeant Jesse said that he forgets that not everyone shares his knowledge and experience with firearms. With a handgun, he said he could “comfortably” shoot someone so many feet away, and pointed across the street, while with a rifle he could comfortably shoot someone much farther away, and pointed to the other side of the fenced off lot on John Street. I suggested to Sergeant Jesse that he might want to rethink using the word “comfortably” when talking about shooting someone, but Sergeant Jesse persisted, citing his extensive training and target shooting experience. Later in the same conversation I suggested to Sergeant Jesse that using the word “comfortable” to describe shooting someone, even a killer, is a little unnerving, when what he really might have meant was “proficient in” or “confident in his abilities to.” Sergeant Jesse said he understood my meaning and would take this point into account in the future.

I noticed at least two or three passers-by taking stock of our conversation, and I thought of all those times I rubbernecked and attempted to eavesdrop on a law enforcement official’s conversation with a civilian. Those kinds of interactions stand out as something serious, fraught, and gossip-worthy. There’s also a nuance and subtlety, not to mention intimacy, to such interactions that doesn’t translate into news stories. Someone in conversation with a police officer in public is usually either 1) a victim of a crime, 2) a witness to a crime, or 3) a suspect in a crime. In speaking to Sergeant Jesse, I became aware of the aura that travels with him and hangs over all his civilian interactions, and how much he seemed to care about those. I thought to thank Sergeant Jesse for his service, but forgot before I walked off. While I did express gratitude for the outreach work he was doing that day (twice), I should’ve gone farther and thanked him for the work he does on a daily basis to keep the citizens of our city safe. When I see police and military officers in public I often think to do this and rarely do because I don’t know them or their work, I’m an introvert, and because authority figures intimidate me, but Sergeant Jesse was easy to talk to and solicitous of my opinions.

Sergeant Jesse and I kept getting slightly off topic from his original question. When I expressed dismay at the presence of guns, even guns in the hands of law enforcement, Sergeant Jesse countered that this is a nation of guns, citing specifically the American Revolution. Were I a better student of history and less of an introvert, I might have pointed out that many European countries endured revolutions and civil wars since the invention of firearms without suffering America’s mass proliferation of guns, gun-related violence, and dumbfoundingly pro-gun legislation. (I do not know where Sergeant Jesse stands on gun control, but I do know he doesn’t think they’re going anywhere.) Sergeant Jesse’s original purpose that day was: 1) to assess the general attitude of the local population with respect to an increased police presence during Pride, and 2) to do some outreach in advance of that increased presence. We both agreed that earlier community outreach would have helped reduce anxiety caused by the presence of police armed with rifles at the event. (Sergeant Jesse said he’d advocated for this before the Orlando shooting.) Sergeant Jesse also took my point that most of the attendees would probably share my level of ignorance that a police rifle equals better public safety in the event of an attack. The primary barrier in our dialogue stemmed from our backgrounds. Sergeant Jesse is an officer, and trusts other officers implicitly with his own life and the lives of others. Sergeant Jesse also used to work in counter-terrorism, and I think it’s fair to say that he’s primed to imagine worst-case scenarios and the skill, technology, and weaponry he can use to combat those possibilities. When Sergeant Jesse said he’d be “comfortable” taking the life of a killer, he meant both proficient and morally justified, whereas I think I’d be more likely to hesitate and experience even a morally justifiable killing as a personal trauma. In addition, however illogical it might be, I am more likely to interpret a heavily armed police presence as a sign of impending trouble than of safety.

I forget how it came up, but Sergeant Jesse started talking about Black Lives Matter. He mentioned it and then quickly pivoted to a story about his own ten-year-old daughter, who I’ll call Little Jessie. Little Jessie came to Sergeant Jesse one night asking if she could stay up late. Sergeant Jesse said no. Little Jessie said she wanted to give her reasons why she should be allowed to, but Sergeant Jesse again said no. This happened once more before Little Jessie accused her father of not giving her a chance to reason with him and, perhaps, change his mind. Sergeant Jesse apologized, said she was right, and allowed her to present her reasons. Though ultimately Sergeant Jesse did not change his mind, Little Jessie told him that, “I just needed to be heard,” which Sergeant Jesse related as a moment of personal insight. “It’s the same with Black Lives Matter,” Sergeant Jesse said. “They just want to be heard.”

“To be heard” is not the primary concern of the Black Lives Matter movement. The BLM movement started in response to a series of killings of unarmed black men (and a black child with a fake gun) by police officers. Some of those men died from the excessive use of physical force, others from gunshots. Sometimes the use of deadly force could be interpreted as a tragic mistake, like in the case of Rumain Brisbon. Sometimes it is simply criminal, like in the case of Walter Scott.

The decision to use deadly force is often made under pressure and fast. The decision relies on quick assessment and instinct, as do a lot of police actions, but these are also prime targets for a phenomenon called implicit bias. Most Americans exhibit some form of implicit racial bias against blacks. If you click that link, you’ll read that the actual implicit racial bias is likely higher than the numbers reported, and that pretty much everyone is afflicted. When fractions of seconds matter, or when you’re taking a quick assessment of a situation and a suspect, an officer is more likely to imagine a compassionate narrative for a white person than a black person. An implicit racial bias can be reduced, but it requires conscious and regular effort, and the permanency and power of these reductions are debatable.

Now I must preempt the rest of this blog post to tell you that what happened on Wednesday, June 22 is that I ran into Sergeant Jesse again. I was on my way to the U District light rail station when he called my name, and I thought, “Shit. We’re going to talk and I’m going to have to confront him with that stuff I wrote AND rewrite my blog post.” Since Friday, I’d been wishing I’d said something in response to his comment about BLM. I didn’t believe it, but I thought there was a chance Sergeant Jesse was saying that the only thing the BLM movement wants is a series of compassionate sit-downs with law enforcement that may or may not result in any tangible action.If this were true, I thought it was a serious dismissal of the movement’s goals. I also thought to challenge Sergeant Jesse’s statement, but instead, that Friday, I let it go. I challenged Sergeant Jesse’s usage of the word “comfortable,” but not this other, more important thing. I was a white man talking to a white officer in a leadership position and failed to correct what I thought was a racially problematic comment. All it would’ve taken was me saying, “I think the movement wants more than just to have their concerns heard,” and maybe Sergeant Jesse would’ve said, “Oh, totally! Wait, what did I say?” and then I would’ve slept better.

I told myself later that I didn’t do it because it was off topic, but we talked about other off-topic subjects. My partner suggested maybe I didn’t challenge him because I was afraid I wasn’t knowledgeable enough on the subject, which is partly true–I’m sure if I talked about racial inequality on a regular basis with my friends or at work I would’ve felt better prepared and at ease on the subject, but I knew enough. Maybe I was afraid that Sergeant Jesse’s attitude towards me might turn. The truth is probably a blending of these things, but most damningly is this: I didn’t have to. I was a white person in relative privacy “letting it slide.” Because I could. Because it was easier. Because even if Sergeant Jesse actually had meant to be that dismissive (he didn’t by the way), it wasn’t my problem. At least it wasn’t my problem in the traditional sense, but it’s my problem because this is something I think about, read about, and want to be better at, and because I view racism as more than just a collection of personal faults. When you start seeing the world and yourself as racist (which, I’m afraid, is the truth) you realize that the work to dig just yourself out from it will be hard and never-ending.

When Sergeant Jesse and I ran into each other again on Wednesday, he told me what had kept him up after our conversation. He said that no one had ever challenged him on the word “comfort” before with respect to shooting someone. He said that had been a symptom of “tough guy” talk, that it made him sound like he’d have no trouble going to sleep at night after shooting someone when, in fact, he would. He related a story of when he was younger and his cousins encouraged him to shoot a woodpecker with a BB gun. He tried to miss and wound up injuring the bird only to watch his cousins excitedly finish the job. I then told him what had kept me up. Sergeant Jesse said that he had meant the comment rhetorically. He added that he’s interested in those sit-downs and he agrees that greater action is needed, even if the progress that results from it moves far too slow.

During our first conversation, Sergeant Jesse demonstrated himself in words and actions to be a person who cares about community perceptions and opinions of law enforcement. He acknowledged that there are bigots and “jerks” in the police force, just as there are in the general population. Sergeant Jesse hates having these people in his ranks because they make it harder for him to build relationships and trust with the communities he polices. Even though he expressed these attitudes, in some ways expressing himself to be an ally, I didn’t challenge him to be a stronger community ally when I thought I should. We are all guilty of racist attitudes and actions because of the society we were born into. It’s the action we take, each of us, regarding these attitudes that redeems us, even if only incrementally.

That first time I met Sergeant Jesse I asked for his business card to pass along to my partner, who frequently interacts with law enforcement in his work as a trauma center emergency department social worker. I planned to write Sergeant Jesse an email thanking him for his service and challenging him on what he said about BLM, but now, because we’ve run into each other again, I’ve revised that as well:

Sergeant Jesse:

Thank you for your offer to use your real name in my blog post. I’m afraid that I’m such a fan of your new nickname and that picture of former Minnesota Governor Jesse Ventura that I’ve decided to keep your anonymity in place.

I’ve already thanked you numerous times for your community outreach, and I hope you know how much I mean it. Talking to a police officer, even a kind and outgoing one, can trigger anxiety in folks who are used to authority figures (not to mention burly peers) not always being on their side. You said that your passion in life is to protect people. I felt that to be true in speaking with you. I really wished I’d thanked you for your service beyond the work you were doing that Friday. I’ve forgotten to do that twice now, and I regret it. Your friendliness allowed me to talk more freely. I should have expressed my gratitude for the work you do to keep our community safe every day. Thank you.

I now know that on Friday, when you said that Black Lives Matter activists “just want to be heard,” you meant that to be a rhetorical statement and not the sum total of the group’s wishes. I do believe you’re someone who thinks about racial disparity in law enforcement, but please consider: If you had stopped a person of color that Friday instead of me and shared a similar conversation, would you have worded that comment the same way? Would you have invited a conversation about the BLM movement, or policing of communities of color in general, without prompting? Listen: I am guilty, too; I believe we all are. I am sometimes more hesitant to talk about matters of race with my friends of color because I am afraid of saying the wrong thing or because I see it as a possible source of tension between us, and why risk it? The results are that some issues only get raised for me when a person of color decides to speak on it to a white person, which is burden in itself, for they risk the same tensions. The way I think of my role that Friday is that I was in public conversation with a receptive, respectful police officer, one who holds a leadership position, an officer who’d already demonstrated himself to be thoughtful on matters of community policing, and I chose not to engage on what we both now know was a misstatement.

I’m sure you’re aware of the disparity in law enforcement and criminal sentencing that disproportionately impacts black individuals. I don’t know exactly what it will take to correct this disparity, but I do know they are symptoms of a society with a long and deep history of racism, both institutional and cultural. To fix these things will take steady, rigorous work. This work must be taken up by organizations AND individuals. Here are a few articles and resources on the subject I’ve found very interesting: (I want to acknowledge that not all of these are specifically about police policies.)

- Slate: Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System

- NAACP Criminal Justice Fact Sheet

- Police Chief Magazine: Implicit Bias and Law Enforcement

- The Atlantic: The Black Family in the Age of Mass Incarceration

Something else I wanted to bring up that didn’t come up in our conversation: I wish we lived in a more compassionately-structured society. I think we have a tendency to combat an increase in crime statistics with an increase in policing and incarceration. We are less likely to fund, say, early drug intervention programs and social services than we are to fund the tools that punish offenders. In addition, we often make those punishments harsher in the hopes of reducing recidivism, which doesn’t really work. This is not exactly my position, but consider the labor hours and cost of an increased police presence this weekend vs. the other things that money could have been spent on towards the same goal: reducing crime and strengthening communities.

As I mentioned, I’m a writer and I’ve written a piece about our interactions on my blog (link provided). Please do not feel the need to respond to this email, but if you do please be aware that I may include part or all of your response on my blog as an update or a future post.

Also, I was serious when I offered to be a resource to you for your own writing. I’m sure you’ve got lots of interesting stories to tell. Thanks again for the work you do and for saying hi a second time, even though it required that I spend all evening revising what I thought was already really a pretty good blog post.